CBC News

September 10, 2019

In the latest season of the CBC investigative podcast Uncover, host Michelle Shephard revisits the unsolved homicide of a Toronto teen two decades after she first covered the case as a cub crime reporter at the Toronto Star.

- Listen and subscribe to Uncover: Sharmini at CBC.ca/uncover or on Apple Podcasts, Google Podcasts or Spotify.

Sharmini Anandavel wanted to buy shoes to match the mauve dress she was going to wear to her Grade 9 graduation.

The 15-year-old was just weeks away from leaving behind junior high when she last left her north Toronto apartment building in June 1999, telling her family she was headed to a new job.

Four months later, her skeletal remains were found in a shallow grave in a wooded ravine, right next to the Don River.

Twenty years after her death, no one has been charged.

But police had a prime suspect from the very night she went missing: A 23-year-old neighbour who lived one floor down from the Anandavels.

Police interrogated him, searched his car and apartment, put him under round-the-clock surveillance and interviewed those who knew him.

He is behind bars today — but not for Sharmini’s death.

II.

Sharmini lived with her parents and two brothers — one older, one younger — in an apartment building in Toronto’s Don Mills neighbourhood.

Developed after the Second World War, Don Mills was originally white and middle class, with clusters of bungalows, manicured lawns and sensible cars.

But over time, it became one of Toronto’s most diverse neighbourhoods — striking in a city famous for its diversity. By the late 1990s, the area was a mishmash of cultures and incomes.

The neighbourhood is bordered by ravines that meander through Toronto. At the centre of it is Peanut Plaza, named for the peanut-shaped parcel of land on which the strip mall sits.

The Anandavels had fled war in their homeland, like many other immigrant families in the community. They had come from Sri Lanka five years earlier, and settled into a highrise on the west side of Peanut Plaza.

Sharmini is shown with her younger brother, Kathees.

Sharmini attended Woodbine Junior High School, a brown-bricked building that housed students in Grades 7, 8 and 9, located just across the street from her apartment. She and her friends would often get lunch at the north end of Peanut Plaza and they’d shop at Fairview Mall, just south of it.

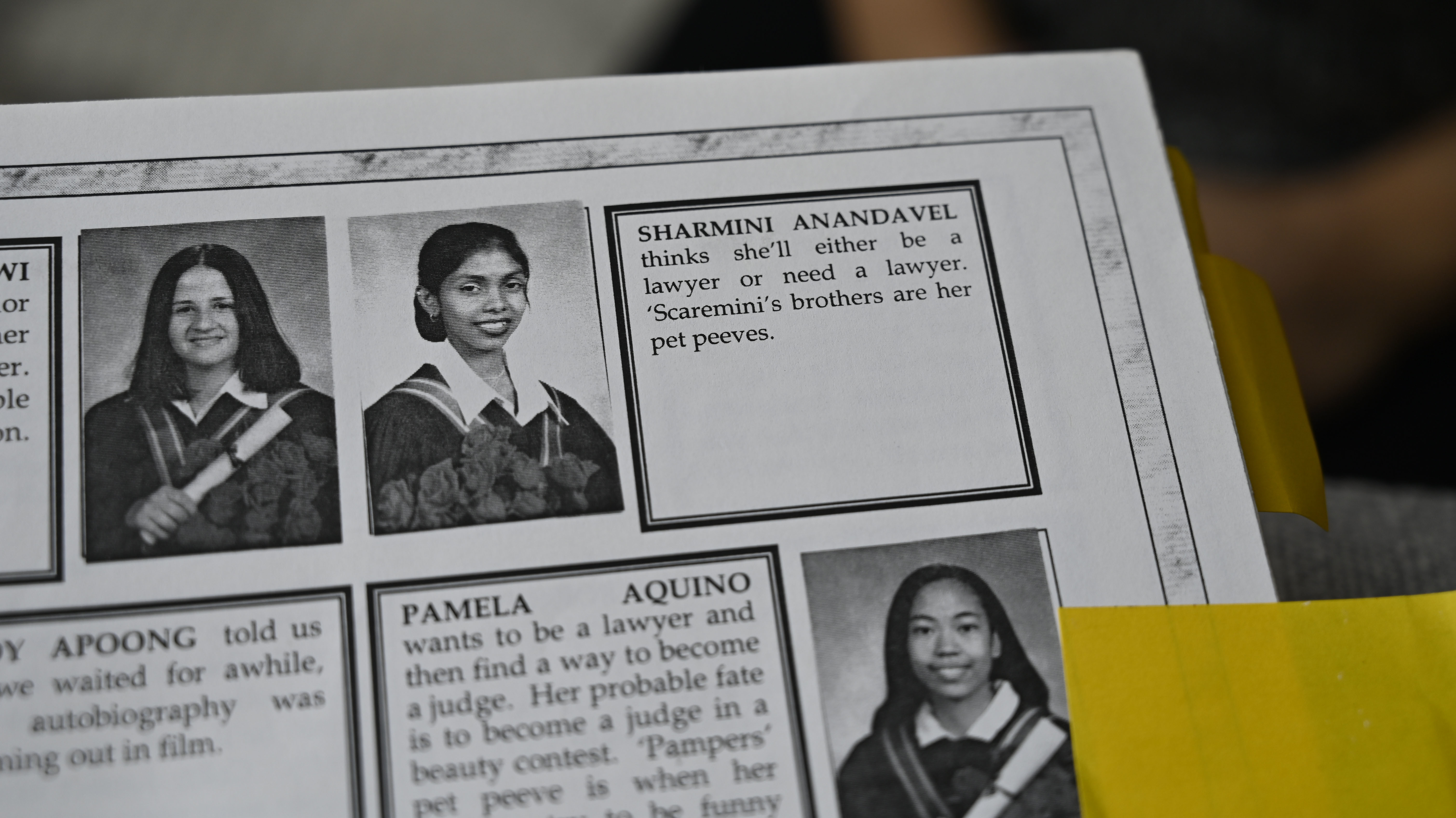

Friends and teachers remember Sharmini as a sweet, bright teen with a wide, infectious smile. She was opinionated, but respectful of others.

“Sharmini stuck out because she was such a vivacious, intelligent, loving person. She wasn’t perfect, right — she’s a teenager. And she could be very sassy, but in a good way. She wasn’t someone that would let people run her over,” Sharmini’s Grade 9 homeroom teacher, Jody White, said in an interview with CBC’s Uncover.

Colin Braddock sat next to Sharmini in homeroom and calls her his “first crush.”

“She was just … so kind. She just had a smile that could light up the room. She really did. And also her personality, she was never mean to anyone,” he said.

Sharmini, left, is shown with two friends in an image from her Grade 9 yearbook. (CBC)

That June, the entire Grade 9 class was excited about their upcoming graduation — and the dance that would cap off the festivities. They’d all be heading to high school in the fall.

Braddock remembers Sharmini being anxious about finding work toward the end of the school year. She wanted to earn some spending money.

On the Friday before her disappearance, Braddock recalls talking to Sharmini about a new job she had just landed. She was really excited. He congratulated her as class let out.

“Nobody really had any jobs back then,” Braddock said. “I was surprised because, I mean, like, the closest thing to a job is a paper route.

“And then, yeah, Saturday happened.”

III.

Sharmini left her home at 9 a.m. on June 12, 1999, on her way to the first day of a new job.

Her younger brother, Kathees, 13 at the time, remembers joking with her about laundry as she walked toward the elevator.

There were conflicting stories about where Sharmini was headed. Her parents said she would be answering phones, at a job arranged by a neighbour in the building. Her friends thought something else.

One witness recalls seeing Sharmini sitting on a bench at Fairview Mall around 10:30 a.m. that morning; another saw her alone in Peanut Plaza, north of the mall, around 11:45 a.m.

She never returned home.

Sharmini is shown at home.

Investigators had their own theory, working off of what her friends had told them: Sharmini thought she was going to work undercover for an anti-drug police operation. They had found a blank job application in her bedroom for something called the Metro Search Unit, an outfit that police later described as “completely bogus.”

The application had a typo and was strangely worded. It only asked for the applicant’s name, birthdate, address and age; there were no spots to jot down an employment history, references or a social insurance number.

Police believe the application was part of a ruse intended to lure her to the park where she was killed — though they waited until six months after Sharmini’s remains were found to reveal this piece of evidence.

Now retired, Matt Crone spent more than 30 years as a police officer and was one of the lead investigators on Sharmini’s case. When the teen went missing, he said the local police detachment reached out to the homicide squad immediately.

Sharmini was set to graduate ninth grade just a few weeks after she went missing on June 12, 1999. (CBC)

Sharmini didn’t fit the profile of a teen runaway. She was close with her parents, did well in school and was looking forward to her graduation. She was steady, not impulsive.

“The interesting thing is — especially when you’re dealing with a young person — is when you talk to the parents, they describe a person for you. You talk to the teachers, they describe a person for you. When you talk to the friends, they describe a person for you. And there are three different people,” said Crone. “But this was odd: you always got the same person with [Sharmini]. This is just a nice kid — hardworking, lots of fun, bright, funny, enjoyed life.”

Sharmini’s disappearance prompted a massive search, involving helicopters, volunteers canvassing at the mall and dozens of police officers.

Sharmini’s parents banged on their neighbour’s apartment door that first night, when their daughter didn’t return home. Sharmini had told them he had helped her secure the job, after all.

No one answered. Stanley Tippett had moved out two weeks earlier.

IV.

Stanley Tippett grew up in a single-parent household in the Toronto area, living in government housing with his mother and two brothers.

Tippett was born with Treacher Collins syndrome, a genetic disorder that affects speech, hearing and facial bone and tissue development, often causing deformities. Tippett’s ears are undersized, with one sitting lower than the other, and his eyes slant down into a slightly sunken facial structure.

As a result, Tippett was in special education classes for hearing impairment and frequently bullied growing up, by classmates and neighbourhood kids. His mother says he was beaten up from time to time; more than once, she had to get the police involved.

By his early 20s, Tippett was living in the same apartment complex as the Anandavel family, just one floor down, with his wife and toddler. In a 1999 Toronto Star story, Tippett said he had a relationship with many of the kids in the building; he would sometimes take them swimming at a nearby pool and taught some of them judo.

Tippett told some of these kids his facial deformities were the result of a mishap that occurred while he was working with the police bomb squad, Crone said.

Stanley Tippett is currently housed at Beaver Creek Institution in Gravenhurst, Ont. (Evan Aagaard/CBC)

Police were interested in Tippett because Sharmini’s parents believe he offered her the job she was heading to on the day she disappeared. But he further piqued their interest, in part because Tippett was known to impersonate a cop. He had a jacket with the word “police” stitched across the back. He’d sometimes carry a nightstick and patrol the building.

“The building itself had a lot of people in it that were new to the country. When he told parents that he was a police officer [or] an ex-police officer, they accepted it,” said Crone. “They obviously felt safe enough to allow their children to go swimming with Stan.”

By the time of Sharmini’s disappearance in 1999, Tippett had a history with police — one that would continue to grow in the years that followed.

In 1998, Tippett told a group of young boys in the neighbourhood that he was a police officer, seizing one of their bikes as part of a supposed operation. A little over a month later, police were called again after the building’s superintendent said Tippett tried to make a fake arrest.

But he first came to police attention in 1991, when a 16-year-old Tippett set fire to a teacher’s desk after stealing her keys and breaking into the classroom.

About a year later, Tippett was accused of following a young woman off a Toronto bus and attacking her. Court records say he approached her from behind, threw an arm around her waist and pointed a pellet gun to her head, pulling her into a laneway and instructing her to lie down.

He was charged and convicted of attempted robbery.

Court records say the quick-thinking teen got away unharmed by saying she had HIV and was menstruating.

V.

A father and son, out for a walk on a crisp Saturday in October in the East Don parklands, stumbled upon human remains. A subsequent police search revealed a skull, some long bones and a mandible, which police used to pull dental records, getting a match for Sharmini.

Crone, out for a motorcycle ride that same day, was quickly on the scene.

The shallow grave was located next to a fallen log, right beside the Don River. The site had been ripped apart by coyotes in the ravine, with Sharmini’s remains strewn throughout the woods. An excavation by forensic archeologists later revealed some hair and blue fingernails — the same colour polish Sharmini was wearing on the day she left home.

But it had been four months since the 15-year-old’s disappearance. And given the summer heat, the proximity of the scene to a coyotes’ den and some flooding in the ravine, police would not be able to find any DNA of the killer.

Police questioned Tippett about Sharmini’s disappearance multiple times over the course of the investigation, though he was never charged.

In extensive interviews with Uncover, Crone revealed for the first time his theory — never tested in court — about what happened to Sharmini and why he still believes Tippett killed her.

Crone said he believes Tippett was “grooming” Sharmini with the offer of a job, specifically choosing something that would have “a certain amount of secrecy attached to it” — one where she’d be discouraged from speaking to her friends or family about it.

“There’s a certain crooked genius to that,” he said.

According to Crone, Tippett stationed Sharmini in the East Don parklands where her remains were later found, giving her some tools and telling her to be on the lookout for drug dealers.

“And when you see it, you call me on your radio and I’ll swoop in with my team and arrest the drug dealers,” Crone speculated.

In Crone’s hypothesis, Tippett left to attend his lawn-cutting job, then returned to Sharmini’s location later, killing her and burying her body. Afterward, he cleaned his clothes and car at his in-laws’ home, then took his car to a local garage to install its new engine.

“I’m absolutely certain … this is the person who did this,” he said.

Now retired, Matt Crone was a lead investigator on Sharmini Anandavel’s homicide. (Evan Aagaard/CBC)

Soon after the first interrogation, Crone said Tippett sold his car to a junkyard for about $10 — despite having just put in a new engine, at a cost of around $1,000.

Police seized the vehicle before it was slated to be crushed. Nothing was found in the car, Crone says, but investigators noted the liner of its trunk had been removed.

Police also believed the phoney application found in Sharmini’s bedroom was given to her by Tippett, Crone said.

The application was created using thermal paper. Coated with a material that changes colour when exposed to heat, it’s commonly used to print receipts in cash registers or debit terminals.

Historically, getting fingerprints from this type of paper was difficult. But in recent years, new methods have been developed — something that could possibly offer a break in the now two-decade-old cold case.

But Uncover‘s investigation revealed that the application — initially sent to the Toronto-based Centre for Forensic Sciences, who couldn’t immediately do anything with it — was improperly stored.

“They stored that in a warm place and the whole thing turned black … So, unfortunately, we lost all of that evidence,” said Crone.

Since Tippett was never charged in Sharmini’s death, Crone’s theory has never been heard or tested in court.

Two of Tippett’s cousins, Rick Steiner and Haig DeRusha, say Stanley has already been condemned by the court of public opinion, assumed guilty, in part, because of the way he looks.

“He was pursued for years following … Sharmini’s murder. And her murder is absolutely tragic — of course it is,” said DeRusha, who is also Tippett’s lawyer.

“But what has happened to Stanley because of her murder is also terrible because … he is a suspect wherever he goes.”

“He has already been treated worse than anybody who would have been convicted,” said Steiner.

“If we’re supposed to be innocent [until] proven guilty, Stanley has not been proven guilty in my estimation, not for … the murder of Sharmini.”

A vigil was held for Sharmini in her north Toronto neighbourhood soon after her remains were found in early October 1999. (CBC)

VI.

In the years following Sharmini’s death, Tippett continued to draw police attention.

In 2000, he was accused of stalking a cashier at a grocery store in Oshawa, Ont., where he had moved after leaving the Don Mills area. He wasn’t charged, but was given a no trespass order for the supermarket and ordered to stay away from the woman.

A few years later, Tippett and his family were living in Collingwood, Ont., a ski town on the southern tip of Georgian Bay, about a two-hour drive north of Toronto. It was here that Tippett was convicted of harassing his female neighbour.

Court documents say that when the 25-year-old rebuffed his romantic gestures, he wouldn’t give up. He would “park in front of her residence and would sit and stare.” He also made false allegations to the Children’s Aid Society about how she treated her young son.

He was given a suspended sentence in June 2005.

Tippett and his family then moved to Peterborough, Ont., where police say he was on their radar “right from the day he arrived,” in part because he was on probation for the Collingwood stalking charge.

“We just had a feeling that he was going to be problems,” recalled retired Peterborough police officer Dan Smith. “And sure enough, he was.”

The first hint of trouble came when Tippett allegedly offered a 12-year-girl a fake job at the YMCA. When she told her mom, her mom called the police. No charges were laid.

A similar interaction played out a short while later, when Tippett approached a young woman at the local Walmart, where she was looking for a job.

“Once again, [it was] a new Canadian, vulnerable. And he says he can get her a job at the YMCA and somehow gets her address,” said Smith. “He starts dropping stuff off at her house.”

Records show Tippett showed up at the woman’s home on at least three occasions, once leaving a birthday card signed “Jason.”

He also told her that her duties at the YMCA would include work on behalf of the police.

When Tippett ran into the woman a few days later at Taco Bell, again looking for a job, he berated her, saying he had already promised her employment.

Court records indicate he even brought an application form with him to the fast-food restaurant.

Suspicious, the woman reached out to the Y directly and was told there were no openings and no employee named Jason. The next call was to police.

“And that’s when the bells and whistles went off,” said Smith. “Holy jeez, what’s this guy doing?”

Police moved to arrest Tippett, searching his home and seizing his van. They found duct tape, rope, plastic sheets, plastic cable ties and a hammer and a knife under the driver’s seat — “all sorts of stuff that could be your abduction kit 101,” said Smith. In Tippett’s home, a pellet pistol was found hidden in the basement.

Tippett pleaded guilty to criminal harassment and was sentenced to two years in prison.

The most serious charge against Tippett — one that keeps him jailed today — came in August 2008.

According to a court ruling, Tippett was driving home just after midnight on the morning of Aug. 6, when he came across two young girls stumbling drunk in the streets. Tippett offered them a ride in his van, dropping one of the girls off at a park. He then drove off with the other, who was 12.

The child was found naked from the waist down outside a school in Courtice, Ont., about an hour’s drive away, by police answering the calls of concerned neighbours who had heard someone screaming “No!” and “Please!”

When police arrived, they saw a man walking toward a red van in the school’s back parking lot. He ignored police commands to stop, jumping into the vehicle and driving away, mounting a curb to do so.

An officer gave chase, but it was eventually called off — it became too dangerous on the town’s sleepy residential streets.

The officer did manage, however, to get the van’s licence plate, as well as a look at the driver. He later identified that driver as Tippett, noting that the features of the man’s head and face were very distinctive.

The van, which was found abandoned in Oshawa, was registered to Tippett.

Police found two used condoms inside the vehicle. And the victim’s clothes were found near the scene at the school. While DNA was collected, there wasn’t enough of it to match it to anybody but the victim.

Still, in December 2009, Tippett was convicted of seven counts related to the attack, including kidnapping, sexual assault and sexual interference.

Stanley Tippett gets into a car outside the Superior Court of Justice in Peterborough, Ont., on Dec. 23, 2009 after being handed a guilty verdict in the kidnap and sexual assault of a 12-year-old girl. (Peter Redman/The Canadian Press)

To this day, Tippett, who pleaded not guilty to the charges, maintains his innocence, saying he, too, was the victim of a crime and was ultimately wrongly convicted.

In his telling of what happened that night, Tippett was giving the girl a ride home when he was carjacked by two men, who threw him out of the vehicle and took off.

Tippett says he landed in a ditch and had to climb out. He then walked a short distance so he could call his wife, who ordered him a cab, which he took to his uncle’s place nearby in order to report the carjacking.

The DNA evidence proves he never attacked the 12-year-old, says Tippett, who agreed to an interview with Uncover because he said he wanted to clear his name in the 2008 sexual assault.

Evidence at Tippett’s trial showed there were traces of semen on the girl’s tank top from two different men, which supports his carjacking claim. Tippett alleges it was these men who sexually assaulted the girl.

But the samples found were very small — millions fewer sperm cells than you would normally see if there was recent sexual activity.

“They brushed it off as nothing but a laundry transfer,” Tippett said.

A forensic expert at Tippett’s trial testified that a laundry transfer — where trace amounts of a substance can transfer from one item of clothing to another in the wash — was one plausible explanation for the two sets of sperm cells on the victim’s tank top.

In his ruling, the judge who found Tippett guilty noted that the victim’s clothing had only her DNA on it.

Tippett filed an appeal, but lost. The appellate judge conceded that while the trial judge erred by not mentioning the men’s sperm cells in his initial ruling, the error was not significant.

In fact, he noted that the male DNA proved nothing. There wasn’t enough of a sample to match it to anyone. It didn’t point to someone else sexually assaulting the 12-year-old, nor did it convict Tippett. It was simply inconclusive.

The other evidence — including witness testimony — was enough to convict Tippett.

In denying the appeal, the appellate judge wrote that Tippett’s carjacking defence was “unbelievable.”

Tippett was declared a dangerous offender in October 2011 and was handed an indeterminate sentence, meaning he could remain jailed for the rest of his life.

“He has showed a pattern of persistent, aggressive behaviour,” Justice Bruce Glass said at the time, noting Tippett was obsessed with sex and would reoffend should he be released from prison.

Tippett was last denied parole in 2018.

But he continues to fight what he calls his wrongful conviction; he is asking for a review of the DNA analysis from Ontario’s justice minister, who has the power to probe anything determined to be a miscarriage of justice.

“I think there are those that can be rehabilitated, you know,” said Smith, the former Peterborough police officer. “But I believe wholeheartedly, 100 per cent, that that man can never, ever step foot in society again without putting people at risk.

“Never ever have I met a man like him — and I’ve dealt with a lot of serious offenders — never have I ever come across a person like Stanley Tippett.”

VII.

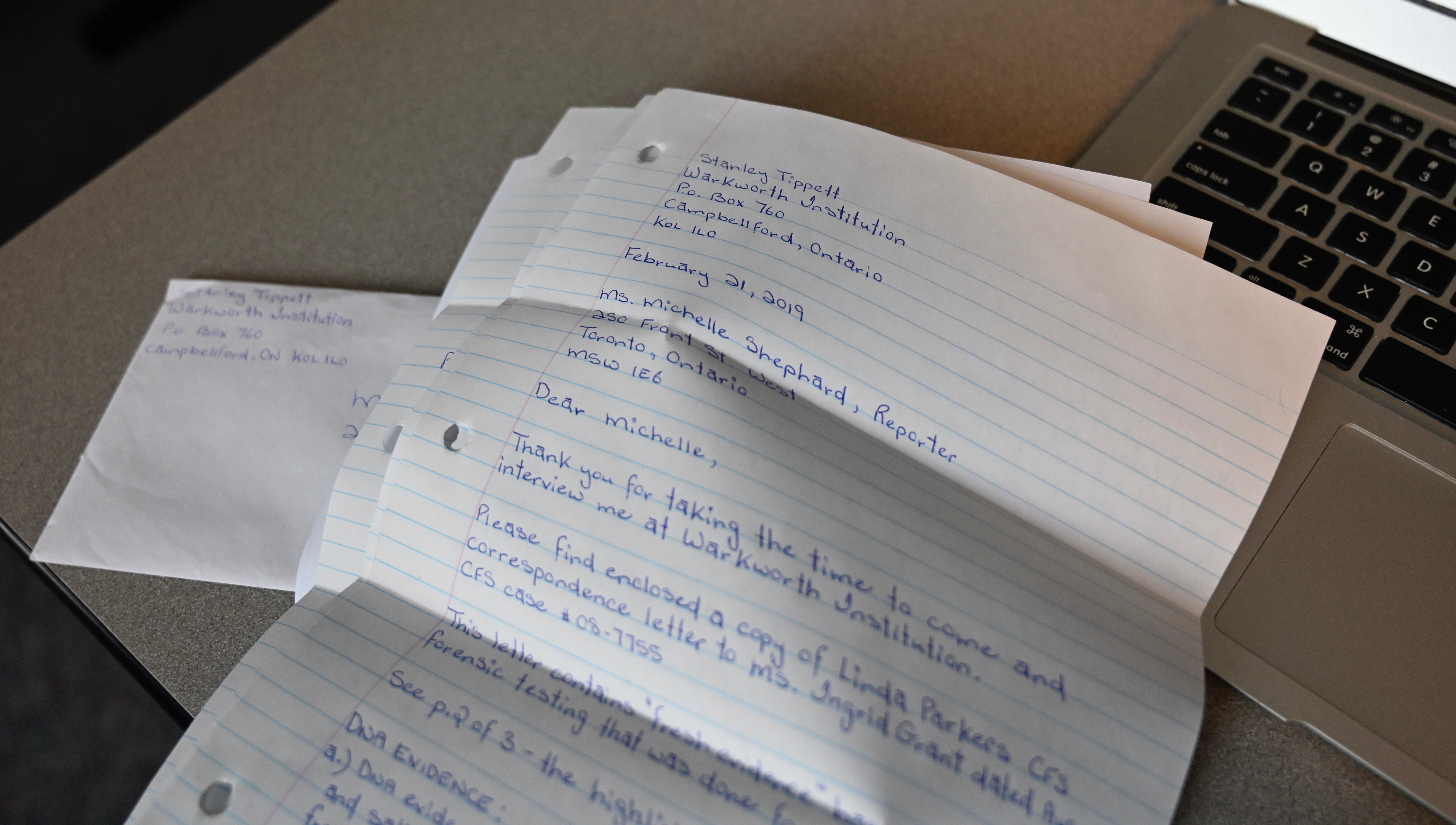

Tippett is currently housed in Beaver Creek Institution, a minimum and medium security prison located in Gravenhurst, in the heart of Ontario’s cottage country. He was moved there from Warkworth Institution, closer to Peterborough, after a number of violent incidents.

It’s probable that Tippett has been targeted while imprisoned, both for his appearance and due to a hierarchy common in prisons: Those accused of sexually assaulting children are often the most despised.

Before the interview begins, Tippett says he won’t talk about Sharmini; he doesn’t mention her by name, instead calling it the “Don Mills incident.” He says he only wants to talk about what he calls his wrongful conviction in the assault of the 12-year-old girl.

For all of his convictions, Tippett has his own version of events.

Tippett corresponded with Uncover host Michelle Shephard over a months-long period, wanting to talk about what he called his wrongful conviction for the 2008 sexual assault. (CBC)

In the Collingwood case, Tippett alleges his female neighbour was actually stalking him. She had an obsession with married men, he said.

“As I was putting my kids to bed, she … disclosed to my wife that she had a problem and that she inherited this problem from her mother. She said that she had a problem going after married men,” Tippett said. “She couldn’t help herself because that’s what her mother did.”

As for the young woman he met at that Peterborough Walmart? Tippett says he was competing for the same job and, after talking to her, it was clear she didn’t deserve it.

She had told him she had just quit another position, he said, and he felt “a little bit jealous” since he had been struggling to find employment. So he falsely directed her toward the YMCA.

When Tippett ran into her at Taco Bell by chance, he reacted strongly, he said, because he frequently went to the restaurant with his family; he worried that if she was hired, she’d meet his family and tell them about his lie.

As for the items found in his vehicle — a hammer, cable ties, rope, duct tape — Tippett says police “took it out of proportion.”

“I had, basically, stuff that I had cleaned my vehicle with,” he said. “People could use a lot of things for different purposes.”

The cable ties, for example, were used to strap down portable TVs for his children, he said.

For the most serious charge, the 2008 sexual assault, Tippett maintains his innocence and said he regrets picking up the young girls. But he asks people to consider the circumstances: It was after midnight and the girls were drunk and on the road.

“I made the mistake of stopping to help someone who I thought was in need of help.”

Tippett’s psychiatric profile — gathered by psychiatrists for both the Crown and defence during his dangerous offender hearing — describes him as a “sensation seeker” and an “impulsive individual” with a “personality disorder.” It says he’s “duplicitous” and a narcissist.

VIII.

Today, the Anandavel family lives in Ottawa, where they moved soon after Sharmini’s remains were found.

Her brothers, Kathees and Dinesh, are now in their 30s and remain close — so close, in fact, they married sisters. They visit their parents often, for meals and other family events.

The middle name of Kathees’s daughter is Sharmini, and he says his son is starting to ask about the girl he sees in pictures around his grandparents’ house.

“One of the things I’ve … always kind of struggled with [is] having kids and telling them that I had a sister at one point,” he said.

Both brothers say they don’t have many memories from the time; they’re forgotten or perhaps blocked from their minds. But both are among those who believe Tippett was their sister’s killer.

Sharmini is shown with her brothers, Kathees, right, and Dinesh, centre, during a birthday party.

Sharmini’s murder — listed as Homicide 36 for 1999 — remains classified as a cold case, meaning there are no leads left to follow in the investigation.

Det-Sgt. Stacy Gallant, who is in charge of cold cases for the Toronto Police Service, confirms his team reinvestigated the killing in 2011 after “new information” came in.

“Unfortunately, between the two investigations that happened, they were unable to bring it to the point where anyone could be arrested or a prosecution could be mounted,” he said.

Gallant declined to specify what new information was brought forward. But the timeline coincides with Tippett’s dangerous offender hearing.

According to former Crown attorney Paul Culver, it is generally more difficult to prosecute a cold case. Witnesses may have died or moved away without a forwarding address, and the passage of time can erase memory; details can be forgotten.

“The test for laying a charge is reasonable prospect of conviction. The test for finding someone guilty is proof beyond a reasonable doubt,” he said. “And somewhere in between, you have to weigh what are the consequences of laying the charge and taking it to the trial.”

Sharmini as a young child.

Sharmini’s death also played out in the aftermath of the exoneration of Guy Paul Morin, who spent 18 months in prison for the 1984 rape and murder of nine-year-old Christine Jessop of Queensville, Ont.

Like Sharmini, Jessop was missing for months before her body was found.

Portrayed as the creepy neighbour, police narrowed in on Morin after he didn’t help search for her or attend her funeral. More than a decade later, he was cleared by DNA evidence.

A subsequent public inquiry into his wrongful conviction condemned the police officers and prosecutors for their tunnel vision — the single-minded belief that Morin was the killer.

Crone said he wonders if that was top of mind in Sharmini’s case, perhaps influencing whether the Crown felt apprehensive about laying charges.

“I came onto this case fresh off of leaving the Christine Jessop reinvestigation. So all the sore points that we kind of got stuck with from Christine Jessop and Guy Paul Morin were still very fresh,” said Crone. “Quite frequently, when we started the investigation, you know, we’d asked the team … ‘Is there any other explanation? Are there any other suspects? Should we be looking at an alternative theory? Should we be thinking of something else?’ And the responses I get were like blank looks going, ‘What, are you stupid?’ … It was kind of overwhelmingly all roads lead back to Stan.”

Crone also said his team knew that in order to charge Tippett, the evidence had to be compelling — and that just wasn’t there.

There were three main holes in the Sharmini case: a lack of forensic evidence; discrepancies about where the teen was going on the day of her disappearance; and the fact that no one had seen her with a suspect that day.

“When I retired, I found myself apologizing to the Anandavel family — that we never solved this, we never resolved this issue for them. I think they deserve resolution for this, which they haven’t had, which nobody’s given them,” Crone said. “So that would probably mean more to me than anything more you could do to Stanley Tippett.”