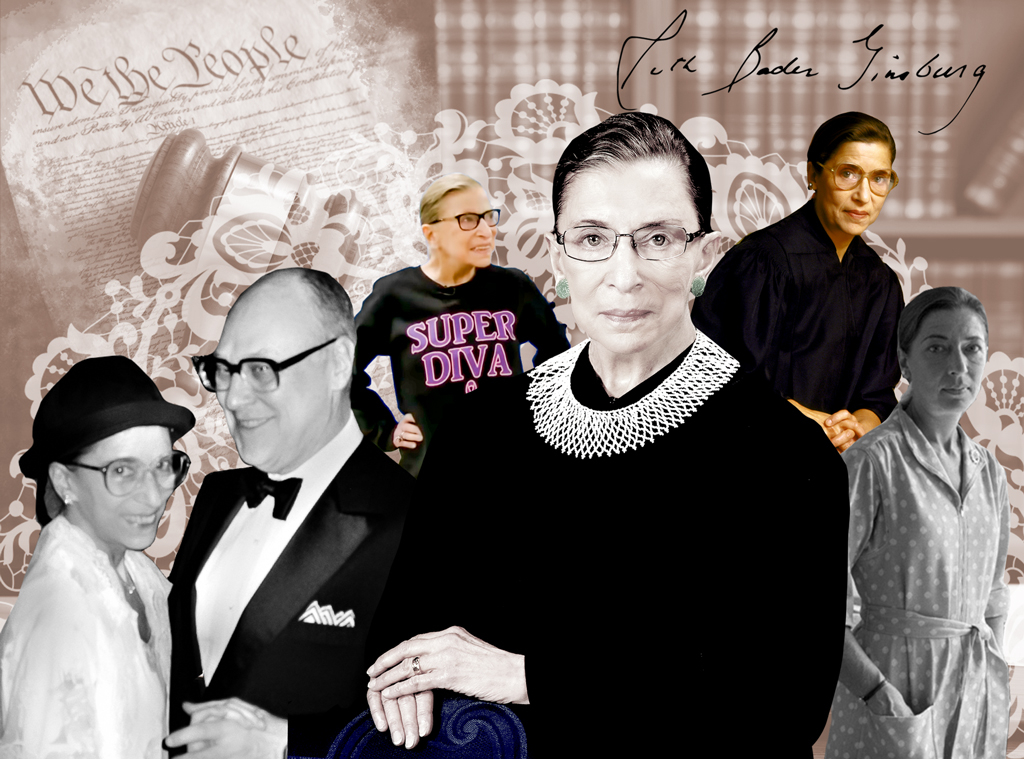

Melissa Herwitt/E! Illustration

Melissa Herwitt/E! Illustration

“If you have a caring life partner, you help the other person when that person needs it. I had a life partner who thought my work was as important as his, and I think that made all the difference for me.”

Ever deliberate and succinct with her choice of words, Ruth Bader Ginsburg encapsulated one of life’s great truths with that statement describing the heart of what made her 56-year marriage to Martin Ginsburg go round.

In fact, it’s possible that Ginsburg, who died Sept. 18 at the age of 87, leaving behind a towering legacy rooted in her trailblazing work to establish truly equal rights in this country, may never have become an Associate Justice of the United States Supreme Court at all without her husband.

But only because her biggest supporter wouldn’t dream of the seat being filled without his brilliant wife getting the opportunity to state her case.

When Associate Justice Byron White announced his imminent retirement in 1993, Ginsburg was largely known for her pioneering legal work on behalf of women’s rights in the 1970s, more so than for her time spent as a fairly centrist federal judge on the U.S. Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit, appointed by President Jimmy Carter in 1980. Subsequently, she wasn’t President Bill Clinton‘s top choice to fill White’s seat.

So Marty Ginsburg—a prominent, well-connected tax attorney and Georgetown Law professor—took it upon himself to make sure Ruth was in the conversation.

“He made up a book of, essentially, recommendations about her,” NPR’s Nina Totenburg, a longtime friend of Ginsburg’s, recalled on Up First over the weekend. “And when she went to see Clinton—you know, she was a very shy and quiet person, but when she performed, she performed. She knew this interview was a performance and Clinton’s aides said afterward that he fell for her hook, line and sinker.”

Clinton, the first Democrat to get to appoint a Supreme Court Justice in 26 years, told reporters at the time, “There were two or three others that I thought were exceptionally well qualified, but once I talked to her, I felt very strongly about her. This is not a negative thing on them.” (It was considered to be a rather sudden decision, one that threw those who expected federal judge Stephen Breyer to get the nod—including Breyer, who had been told to start drafting an acceptance speech. He ended up as Clinton’s pick in 1994.)

But the 42nd president wasn’t the only one who was instantly impressed by Ruth Bader Ginsburg.

Lynn Gilbert

Joan Ruth Bader, who started going by her middle name when there was another Joan in her elementary school class, met Martin Ginsburg at Cornell University in the fall of 1950 when she was 17, the pair introduced by mutual friends who thought they’d be safe company for each other, since both had significant others at different schools at the time.

Martin—or Marty, as most called him—was the Brooklyn-born, Long Island-bred son of self-made department store executive Morris and his vibrant wife, Evelyn. He was tall, athletic and gregarious, a star of Cornell’s varsity golf team who would drop chemistry as a major because labs interfered with his tee times. And sure, he had a girlfriend at Smith, but he had asked his roommate, who dated one of Ruth’s close friends, to arrange an introduction. He and the petite, serious co-ed, whose sport of choice was horseback riding, became fast friends, talking about “anything and everything,” though the situation didn’t immediately turn romantic.

“Ruth was a wonderful student and a beautiful young woman,” friend Marc Franklin recalled to Ginsburg biographer Jane Sherron De Hart. “Most of the men were in awe of her, but Marty was not. He’s never been in awe of anybody.”

But that didn’t mean Marty wasn’t falling for her. Soon, the Smith girl was in the past and he set his sights on Ruth, who was hesitant to get serious with one of her closest friends—especially one who, though she loved his energy and sense of humor, perhaps wasn’t quite as focused as she was.

Whatever Ruth’s reservations may have been, they were behind her by her junior year. “Marty was most unusual. He was the first boy I ever met who cared that I had a brain,” she said at the Aspen Ideas Festival in 2010. “And he always thought I was better than I thought I really was.” (And in the early 1950s, with McCarthyism enraging both of them, she had realized that their politics were also a match.)

They planned to take on the world together, starting with graduate studies, and that’s basically how Marty ended up enrolling at Harvard Law School. He had considered medicine, but that didn’t interest Ruth, and Harvard Business School didn’t accept women. Harvard Law was somewhere they could both go. Ruth, with one year left to go at Cornell, would visit Marty in Cambridge, sometimes sitting in on his first year courses.

Ruth graduated from Cornell in 1954 and married Marty that June 23, her in-laws gifting the bride her own set of golf clubs. Evelyn discreetly slipped the bride some ear plugs, saying, “I am going to give you some advice that will serve you well. In every good marriage, it pays sometimes to be a little deaf.” Ruth wrote in a 2002 essay for the anthology The Right Words at the Right Time that she took her mother-in-law’s advice to heart, poetically noting, “Tempers momentarily aroused generally subside like a summer storm.”

The next day the newlyweds took off (via ocean liner) for a driving tour of Western Europe. First they moved to Fort Sill in Lawton, Okla., for a year so Marty could fulfill his ROTC obligations, having signed up for another two years when the Korean War broke out. Ruth got a job as a clerk in the local Social Security Office, where her radar for injustice was sparked when she saw firsthand how Native Americans were routinely denied government benefits, often because they didn’t have official birth certificates.

“We had nearly two whole years far from school, far from career pressures, and far from relatives to learn about each other and begin to build a life,” Marty recalled, per De Hart. They spent their evenings reading the classics (Nabokov had been one of Ruth’s literature professors) and listening to music, especially opera.

They also welcomed daughter Jane Carol Ginsburg on July 21, 1955.

Ginsburg’s own mother, Celia, died of cancer two days before Ruth’s graduation from James Madison High School in Brooklyn. The teen missed the ceremony to stay home with her father, Nathan, and her honors and medals were mailed to her. According to De Hart’s 2018 biography Ruth Bader Ginsburg, Kiki—as her mom and dad called her—would always wear Celia’s circle pin on her suit lapel for important occasions, any time she felt her mother would have been proud.

When she was announced as Clinton’s Supreme Court pick in June 1993, Ginsburg invoked her mother, saying, “I pray that I may be all that she would have been had she lived in an age when women could aspire and achieve and daughters are cherished as much as sons.”

The commander in chief was in tears.

Felicity Jones’ Advice From Ruth Bader Ginsburg on Playing RBG

In 1956, Ruth joined Marty at Harvard Law as one of nine women in a 500-student class, buoyed by a Cornell faculty member’s recommendation that she was “attractive, friendly, dignified, and modest almost to the point of reticence. She is not, however, one who evades decision or action when they are required.” She had earned a scholarship when she was Ruth Bader and, before she enrolled, Harvard asked to review her father-in-law’s financials upon finding out she had become “Mrs. Ginsburg.”

The school revoked what had been a need-based scholarship and Morris Ginsburg ended up happily covering his daughter-in-law’s law school tuition. Ruth was understandably incensed at what she figured would never have happened to a newly married man, even if he had a rich father-in-law—and though she ultimately rationalized that a need-based fellowship should indeed be reserved for those in need, the experience would only add more fuel to her lifelong fire regarding the importance of blotting out discrimination on the basis of sex for good.

Ruth—spoiler alert—flourished in her first year at Harvard, whatever obstacles she faced during the day running into Marty’s relentless optimism for her prospects at night, when he’d often whip up an elaborate dinner, complete with chocolate souffles for dessert. (He would remain the resident cook in the family, Ruth secure in the knowledge that her tuna casserole would play no role in making the world a better place.) He also shared child care duties, another example of Marty’s anomalous ways in the patriarchal 1950s (though when she heard that another young couple in Cambridge were divorcing, Ruth immediately hired their former nanny, who looked after 14-month-old Jane until 4 p.m.).

Marty “believed in me more than I believed in myself,” Ruth told De Hart. “He was always so secure within himself that he never regarded me as a threat.”

In December 1957, however, Marty was in a car crash. He recovered quickly from that, but not long after that he discovered a lump, and was diagnosed with testicular cancer. Ruth balanced her coursework with being there for her husband, who would undergo two surgeries and radiation. She kept him updated on his third-year studies (as did friends who took turns holding bedside tutorials for Marty) and cared for Jane at night.

“So it was after 2 o’clock [a.m.] that I started whatever was needed for my own classes,” Ginsburg recalled to the Washington Post in 2013. “I came to realize that I didn’t need a whole lot of sleep and I could stretch my day.” In a different interview, she quipped, “I grew confident in my ability to juggle that semester.”

Happily, Marty made a full recovery, with many people who knew Ruth at the time not even aware that her husband had been sick, so efficient and even-keeled she had remained throughout. After earning his J.D. in 1958, graduating magna cum laude, Marty was offered a job in New York at Weil, Gotshal & Manges.

So, the family moved that summer—but Ruth seemingly didn’t miss a beat, tying for No. 1 in her class at Columbia Law School, where she was one of five Kent Scholars in the class of 1959, and becoming the first woman to ever be on both the Harvard and Columbia Law Reviews.

AP Photo/Dennis Cook/Shutterstock

“That’s my mommy!” Jane announced to the crowd as Ruth, tied for No. 1 in her class, graduated in 1959.

And then one group of men after another at New York’s prestigious law firms couldn’t see the point of hiring this young mom, decorated scholar and promising legal mind that she was. In 1960 she was turned down for a clerkship with Supreme Court Justice Felix Frankfurter, despite glowing recommendations from Harvard Law and Columbia Law faculty.

“I struck out on three grounds,” Ginsburg recalled in a speech at Harvard Law School in 1993. “I was Jewish, a woman, and a mother. The first raised one eyebrow; the second, two; the third made me indubitably inadmissible.”

Finally, Columbia Law professor Gerald Gunther insisted to Judge Edmund L. Palmieri of the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of New York that he hire Ruth as a clerk—or he’d never send another Columbia graduate Palmieri’s way. (Gunther also promised to send another student along if Ruth didn’t work out.)

Ruth remained with Palmieri for two years, did legal research at Columbia and then was hired as a professor at Rutgers Law School in 1963—earning less than her male colleagues because she had a husband who made good money. She and Marty welcomed son James Steven Ginsburg on Sept. 8, 1965.

She’d go on to become the faculty advisor for the Women’s Rights Law Reporter at Rutgers in 1970, the first law journal devoted solely to that subject, and serve as co-director of the Women’s Rights Project at the ACLU.

Making history was soon to follow, Ginsburg chipping away at gender-based discrimination on behalf of women and men (she preferred to use the word “gender” rather than “sex,” determining it proved less distracting for the male judges she regularly faced) in winning five out of six cases that she argued before the Supreme Court.

“We wanted to say the law shouldn’t pigeonhole people, that man or woman should be able to do whatever his or her talents made right for that person,” Ginsburg told the National Portrait Gallery in 2015.

The dignified highs and frustrating lows of her journey were dramatized in the 2018 biopic On the Basis of Sex, starring Felicity Jones and Armie Hammer as Ruth and Marty—who together took Moritz v. Commissioner of Internal Revenue to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 10th Circuit. In November 1972, the court sided with the couple’s assertion that a tax deduction that was available to women and previously married men for the cost of a caregiver, but was denied to a never-married man, was a violation of the Constitution’s Equal Protection Clause.

In fact, it was Marty’s nephew Daniel Stiepleman, a screenwriter, who thought the story of their extraordinarily equal partnership would make for a good movie. He focused on Moritz because, as he told The Wrap, though it wasn’t one of Ginsburg’s landmark cases, “the political and the personal were intertwined.”

“‘Well, if that’s how you think you want to spend your time,'” Stiepleman recalled Ginsburg’s reaction, talking to IndieWire. She would end up advising them as they made the movie, especially when it pertained to getting the legal particulars right. For instance, she insisted that the script should have Marty bringing Ruth the Moritz case, as it happened in reality, not the other way around for dramatic effect.

Focus Features

“I got in touch with people who knew Marty,” Hammer recalled. Skeptical that Ginsburg’s late husband could be as good as everyone said he was, “they said, ‘He was better!'”

The actor continued, “In the ’50s, ’60s, ’70s he was able to subvert the gender norms, cook, clean, do whatever was required. That’s how he exercised his strength. He loved what he was doing, he relished it. Usually a strong man is domineering, but he was willing to be symbiotic and do what was necessary to sustain and foster his family. There would be no Ruth without Marty. He knew his wife was capable of changing the world, and he would do whatever it took.”

Ginsburg taught at Rutgers until 1972, then returned to her alma mater, becoming the first female tenured professor at Columbia Law School. In October 1993, Jane Ginsburg—who got her J.D. from Harvard in 1985 and also became a law professor at Columbia—honored her mother in Cambridge with an award for “serving as a model for generations of Harvard Law students.”

Blinking back tears, Ginsburg told the audience of nearly 700 alumnae, “An award from one’s child, as all parents here know, is something truly to cherish.”

Illustrating the progress she’d seen since her first days as a young lawyer who couldn’t get a job because she was a working mom (or trying to be), she added, “Just last week, the Supreme Court completed a notable renovation of the robing room. Looking to the future, the Court installed for the first time a women’s restroom, equal in size to the men’s.”

Marcy Nighswander/AP/Shutterstock

When she was appointed to the Supreme Court, Marty at her side as she was sworn in on Aug. 10, 1993, the 60-year-old Ginsburg joined Justice Sandra Day O’Connor, a Reagan appointee, as the only other woman to ever sit on the bench. She was also the first Jewish member of the Court since Abe Fortas resigned in 1969.

“I have been supportive of my wife since the beginning of time, and she has been supportive of me,” Marty told the New York Times around that time. “It’s not sacrifice; it’s family.”

The proud husband always kept his sense of humor about him as far as his wife’s considerable accomplishments went. “As far as I can tell based on only 24 months’ experience,” he said in a speech he delivered in 1995, “the only duty of a Supreme Court spouse is to avoid stupidity in public appearances. This is not always an easy task.”

To the New York Times in 1997, asked about his storied cooking talent and Ruth’s lack of it, he cracked, “As a general rule, my wife does not give me any advice about cooking, and I do not give her advice about the law. This seems to work quite well on both sides.”

Meanwhile, Ginsburg became a reliable liberal-leaning vote for the Supreme Court, her dissents becoming as famous as her majority opinions, but she was also full of surprises.

Doug Mills/AP/Shutterstock

The Washington Post noted in 2013 that the key chain Ginsburg used for her office key bore the message, “With best wishes, Strom Thurmond,” a nod to since-bygone civility and perhaps a reminder of what she was fighting for, since Thurmond, who served in the Senate from 1956 until 2003, was a prominent segregationist who deserved opposing at every turn.

And then there was her friendship with Justice Antonin Scalia, her ideological opposite on the court but an intellectual peer and fellow opera lover. (In fact, they ended up the subject of their own opera, Scalia/Ginsburg, which premiered in 2014.) Talking to the Post in 2013, Scalia called Ginsburg “fearless.” He added, “I mean, she can be tough; you don’t push her, especially on those issues she cares a lot about. But she’s otherwise a very gentle, likable and sunny person.”

In fact, she and Marty spent many a New Year’s Eve with Scalia and his wife, Maureen, Marty often cooking up whatever meat Scalia had brought back from a hunting trip.

“I’m amazed at how well she has done without Marty,” Scalia also told the Post. “They were married a long time, a long, long time, and he was devoted to her.”

When Scalia died suddenly in February 2016, Ginsburg said that he “described as the peak of his days on the bench an evening at the Opera Ball when he joined two Washington National Opera tenors at the piano for a medley of songs. He called it the famous Three Tenors performance. He was, indeed, a magnificent performer. It was my great good fortune to have known him as working colleague and treasured friend.”

She called the prominent conservative “a jurist of captivating brilliance and wit.”

Describing what it was like when he and co-star Jones went to Ginsburg’s private chambers at the Supreme Court to meet her for the first time, Hammer recalled to IndieWire, “Everything she says can be interpreted as law. She lays down a public record; there are ramifications to what she says. We took her out for dinner, gave her a glass of wine, and had a great time. She’s funny; a wry, dry sense of humor came out.”

Focus Features

Added Jones, “She was immediately captivated by Armie Hammer. You could see the joy in her face and the love she had for Marty. It was about getting to know her on a personal level. She was involved in every phase, gave meticulous notes on every draft.” Ginsburg even gave the tall, sandy-haired actor (who does bear a striking resemblance to young Marty) a copy of her late husband’s recipe book, Martin Ginsburg: Chef Supreme, which he dutifully sampled.

Days before he died of cancer at the age of 78 on June 27, 2010, Marty Ginsburg wrote his wife a letter on the occasion of their 56th anniversary, shared by Jeffrey Rosen in his 2019 book Conversations With RBG. “My dearest Ruth,” he began, “You are the only person I have loved in my life, setting aside, a bit, parents and kids, and their kids. And I have admired and loved you almost since the day we first met at Cornell…What a treat it has been to watch you progress to the very top of the legal world.”

Karin Cooper/Liaison/Getty Images

He acknowledged that he only had so much time left, and that he was debating whether “to tough it out or to take leave of life because the loss of quality now simply overwhelms. I hope you will support where I come out, but I understand you may not. I will not love you a jot less.”

She returned to work the day after he died, as it was the last week of the term, having returned the support Marty gave her at every turn.

A few weeks later, talking to Rosen at the Aspen Ideas Festival, asked for some secrets as to her “remarkably happy marriage,” Ginsburg explained, “Marty and I lived happily together for 56 years. And on the division of labor in our household, my daughter was asked by a reporter, soon after my nomination, ‘Well, tell me what is life like in your house?’ And she said, ‘Well, my father does the cooking and my mother does the thinking.’ Not true at all, because Marty was the smartest man I knew. Marty attributes his skills in the kitchen to two women—one was his mother, and the second, his wife.”

Unfortunately, he didn’t live to see his wife become the superstar he always considered her to be.

Chip Somodevilla/Getty Images

Over the past decade, as more and more people tuned into just how heroic her life’s work had been (and how she wasn’t getting any younger), Ginsburg became a full-fledged celebrity, lovingly impersonated on Saturday Night Live by Kate McKinnon (“that’s a Ginsburn“) and the subject of both the critically acclaimed documentary RBG and On the Basis of Sex in 2018. Her storied daily workout routine became the subject of rapt fascination, Stephen Colbert joining her in the gym for a Late Show bit in 2018 that naturally ended with Ginsburg leaving him in the dust.

And, though she had to ask for clarification of what it meant, she earned the nickname “Notorious R.B.G.,” a tribute to her fearless—some might say badass—commitment to expanding constitutional rights and the deliberate, cool manner she had gone about effecting real change. Her keen intellect sometimes showed itself in the form of deadpan humor, made all the more cutting by her slight frame and quiet thoughtfulness, Ginsburg preferring to pause while she gathered her considerable thoughts.

If the attention usually reserved for Angelina Jolie or Lady Gaga (both big RBG fans) seemed random, it also marked one of the all-too-rare times that a person not known for singing, acting, reality shows or other common entertainment activity was in the spotlight for her contributions to society.

In 2013, questioned about her decision to read her dissents from the bench in five cases that term (when once would be a rare occurrence), Ginsburg told the Washington Post, “This court deals with what’s on its plate, and last year we had a lot of cases where I thought the court was egregiously wrong.”

David Souter, who served on the Supreme Court with Ginsburg until his retirement in 2009, later called her a “tiger justice.”

Before the spread of the novel coronavirus resulted in business-as-usual shutting down all over the country, Ginsburg had been regularly making an average of two public appearances a week.

Her annual routine, with Marty and then on her own, included spending a week with her kids and four grandchildren in Santa Fe, N.M.—where she enjoyed the city’s world-class summer opera program. Jane, who inherited her father’s skills in the kitchen, would whip up big family meals and the conversation would last into the wee hours.

In recent years, slowed but never sidelined for more than a few days at a time by several bouts with cancer and a variety of other medical issues, Ginsburg seemed both increasingly fragile and yet somehow indomitable, the importance of her longevity becoming more urgent with every illness she was able to power through.

There were some who wanted her to retire while President Barack Obama was in office so that he could appoint her successor and keep her seat a liberal one. She said in 2013 that she didn’t intend to step down, but also that, at 80, she was taking it one year at a time.

Ginsburg ultimately stayed put not least because she (like so many others) mistakenly thought that another Democrat would succeed Obama, but also because she was still physically able to do the job she swore to do in 1993—uphold the U.S. Constitution and, whenever she could, help make this country a fairer place for all of its inhabitants.

Ed Bailey/AP/Shutterstock

Knowing full well what it had done for her, she was a stalwart champion of love and partnerships, officiating at numerous nuptials and, in 2013, becoming the first Supreme Court Justice to preside at a same-sex wedding.

“It was a wedding of two people deeply in love with each other and at last able to make their shared lives a lawful relationship,” Ginsburg told Rosen at the National Constitution Center that year. “It’s one more example of what I see as the genius of our Constitution…The idea of ‘We the People’ has become more and more embracive.”

She officiated her final wedding ceremony just a few weeks before she died, the ailing justice sporting a festive black and white collar over her judge’s robe for the occasion.

“2020 has been rough, but yesterday was Supreme,” tweeted the bride, Barb Solish, who, according to the AP, works for the National Alliance on Mental Illness in Washington, D.C. Her new husband, Danny Kazin, is with the Democratic Congressional Campaign Committee. Few details were released, but one of the families has a good friend in High Court places.

Ginsburg had a core description of marriage she would read at the nuptials she officiated through the years, inspired by her own love affair that lasted for more than half a century—and which certainly never ended in her heart.

Rosen, who asked the justice to officiate his own wedding in 2017, shared her draft in his 2019 book: “Your commitment is rooted in a deep appreciation of each other’s talents and experiences,” Ginsburg wrote. “You have learned the importance of patience, of good humor, and of the joy you bring each other. May the love you bear, each for the other, ever make of the two of you magically more—wiser and richer in experience, happier than either would be alone.”

Wisdom for the ages, courtesy of Ruth and Marty.